Smarter Decisioning for Fintech Growth

Fintechs are redefining lending, payments, and financial services—but scaling successfully means managing risk, preventing fraud, and maintaining compliance without adding friction. Fast, seamless digital experiences require smarter, data-driven decisioning.

GDS Link empowers fintechs with AI-driven automation, real-time risk monitoring, and adaptive fraud prevention, ensuring secure, compliant, and scalable financial services.

How GDS Link helps fintechs

scale securely

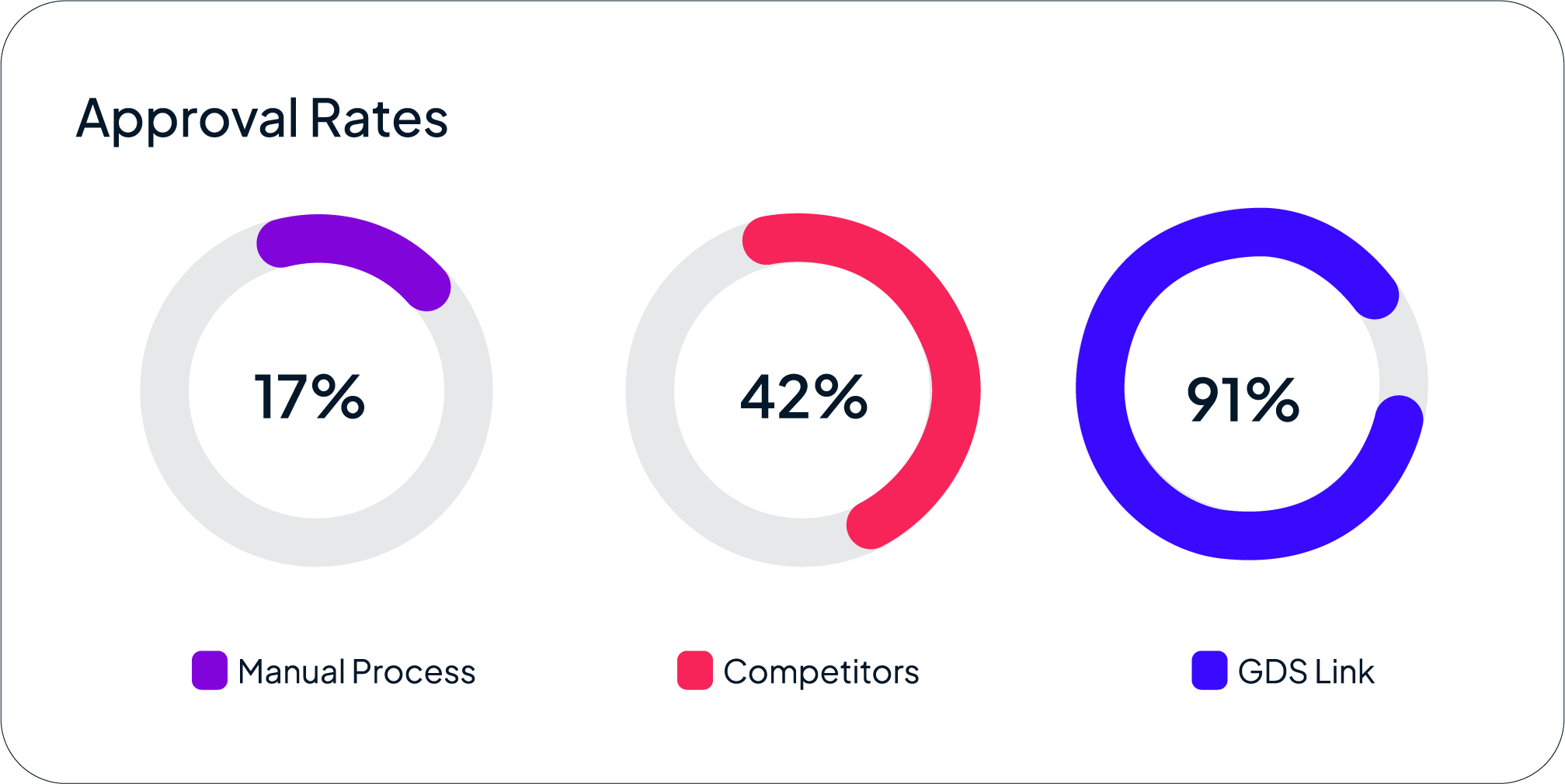

Accelerate approvals and improve borrower experience

AI-Powered Lending Decisions: Automate originations with real-time risk scoring and alternative data.

Seamless Digital Onboarding: Reduce friction and optimize approval rates for new customers.

Data-Driven Decisioning: Approve more borrowers without increasing risk exposure.

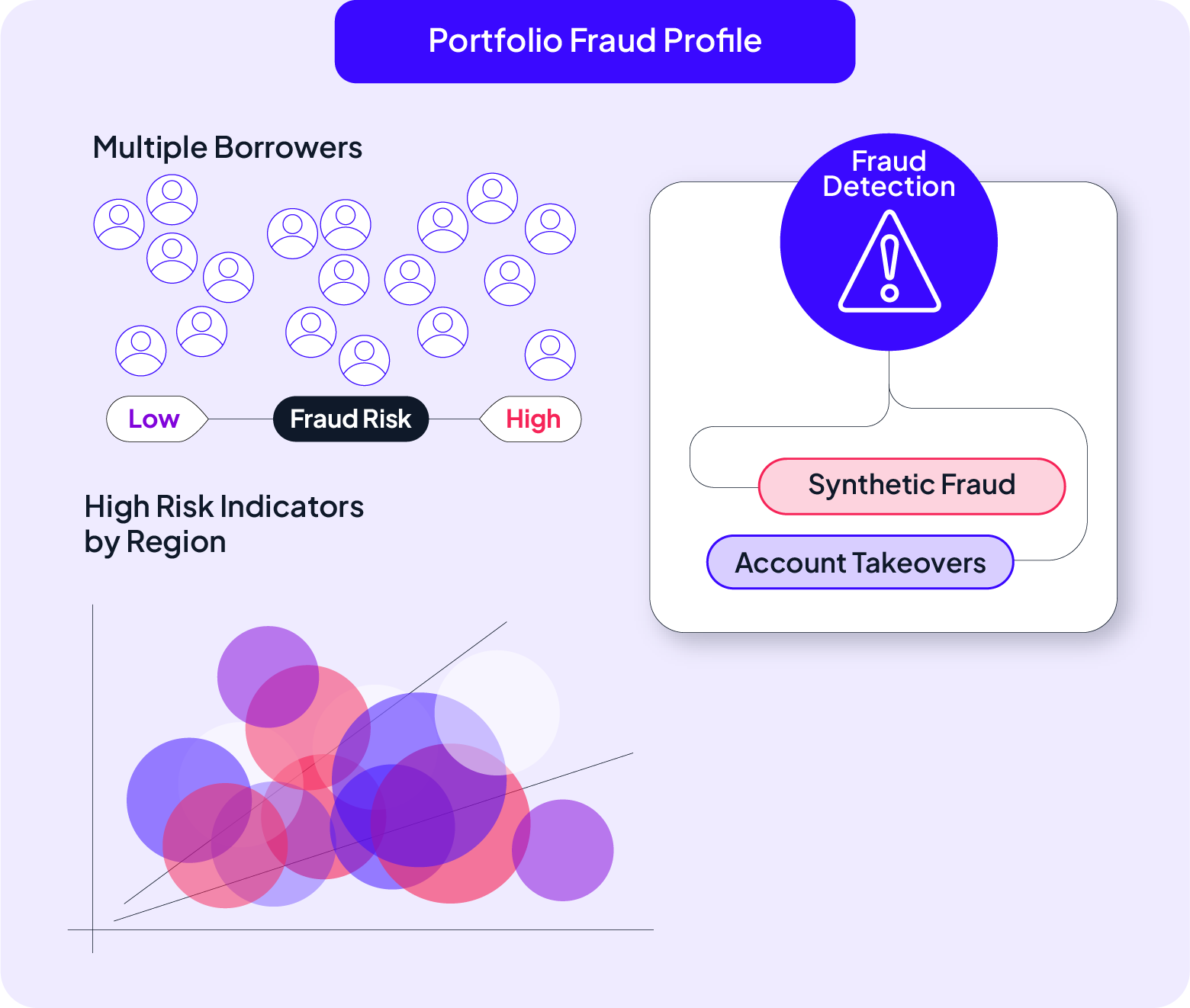

Fraud mitigation for

digital-first lenders

AI-Powered Risk Monitoring: Detect and stop application fraud and transaction anomalies.

Behavioral Analytics: Analyze borrower behavior in real-time to flag suspicious activity.

Seamless Identity Verification: Ensure security without adding unnecessary friction.

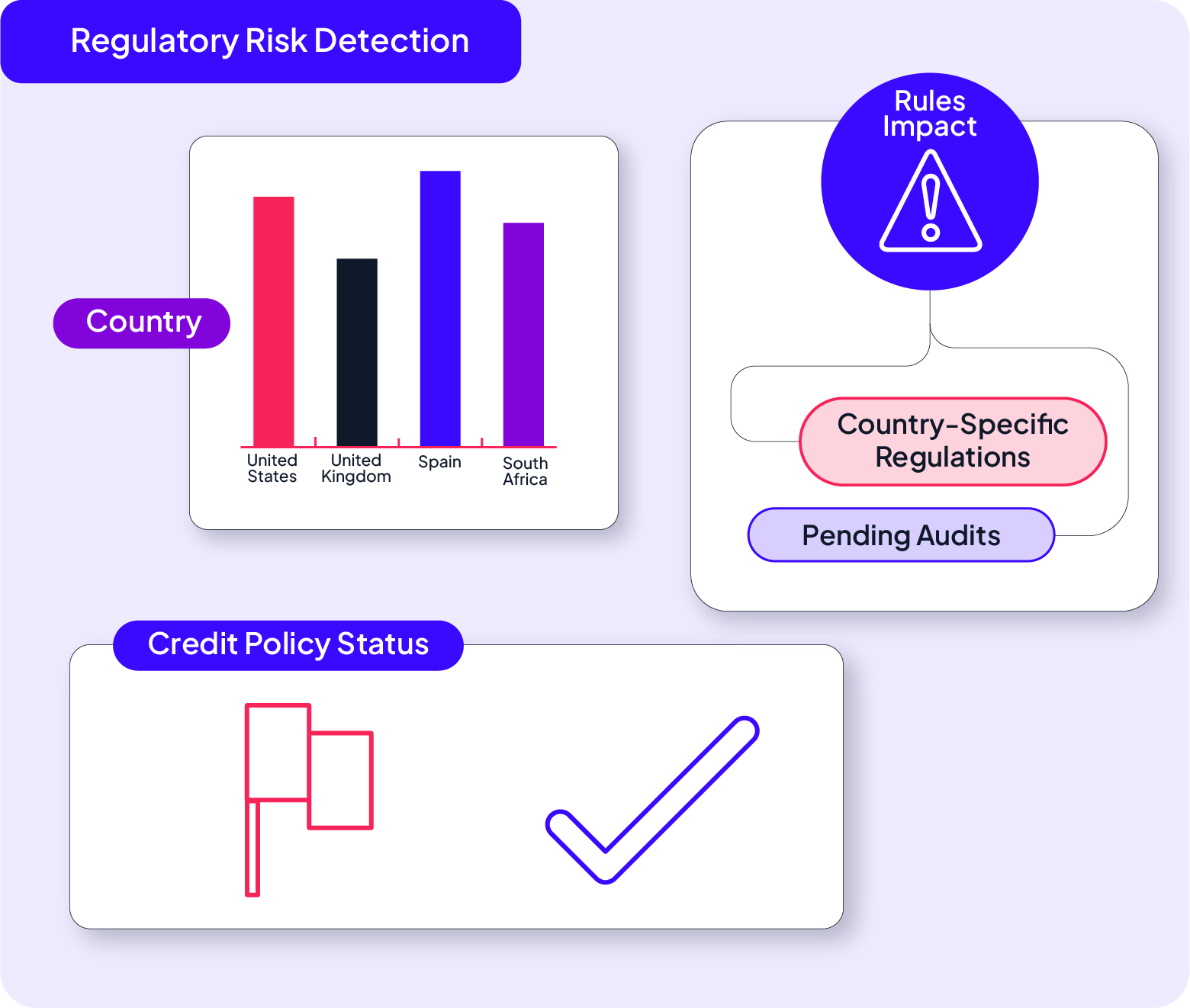

Compliance automation to navigate complex regulations

Real-Time Policy Enforcement: Maintain compliance with automated regulatory tracking.

Audit-Ready Reporting: Streamline compliance documentation with AI-generated reports.

Adaptive Compliance Management: Instantly adjust risk policies to match evolving regulations.

How GDS Link helps fintechs solve their biggest challenges

Fintechs must approve borrowers in real-time while avoiding risky applicants that can drive up losses. GDS Link’s AI-powered originations platform integrates alternative credit data, applies machine learning risk models, and automates underwriting to increase approvals without unnecessary exposure.

Learn moreFraud is one of the biggest threats to digital-first lenders, from bot-driven application fraud to transaction-level anomalies. GDS Link’s fraud prevention suite analyzes real-time behavioral patterns, detects suspicious activity, and prevents high-risk transactions—all without adding friction to the borrower experience.

Learn moreRegulatory scrutiny on fintechs is increasing, and non-compliance can lead to heavy fines and operational shutdowns. GDS Link’s automated compliance tools enforce real-time policy adherence, generate audit-ready reports, and adapt instantly to new regulations, keeping your business compliant without disrupting growth.

Learn more"GDS Link’s latest platform enhancements have been instrumental in optimizing our risk management processes. As we continue to grow and provide fast, hassle-free personal loans, their advanced credit decisioning capabilities are helping us deliver on that promise with confidence."

Own and scale your fintech's growth strategy.

Seize every opportunity.

Unlock the full potential of your fintech operations with AI-driven risk management and intelligent lending automation. Contact us today to see how our platform can help you drive smarter, faster lending decisions.